By Gary Gulezian

June 28, 2023

On a day in early May of 2021, soon after the emergence of new leaves on our backyard trees, my wife Greta and I noticed that the Beech leaves looked strange. They were leathery, thickened and crinkled. As we explored our woods further, which are extensively populated with both young and mature Beeches, we found that the vast majority of Beech trees and their leaves were similarly afflicted.

After a short internet search, it appeared that the leaves may have been exhibiting the symptoms of Beech Leaf Disease (BLD), however, other Beech diseases can display similar characteristics and BLD had never been reported in Maine. We contacted the Maine Forest Service, sharing our observations and some photos, which prompted specialists from the Maine and the U.S. Forest Services to make a visit to our property. Samples of the Beech leaves were collected and later analyzed at the Connecticut Agricultural Field Station which confirmed that the trees were indeed infected with BLD.

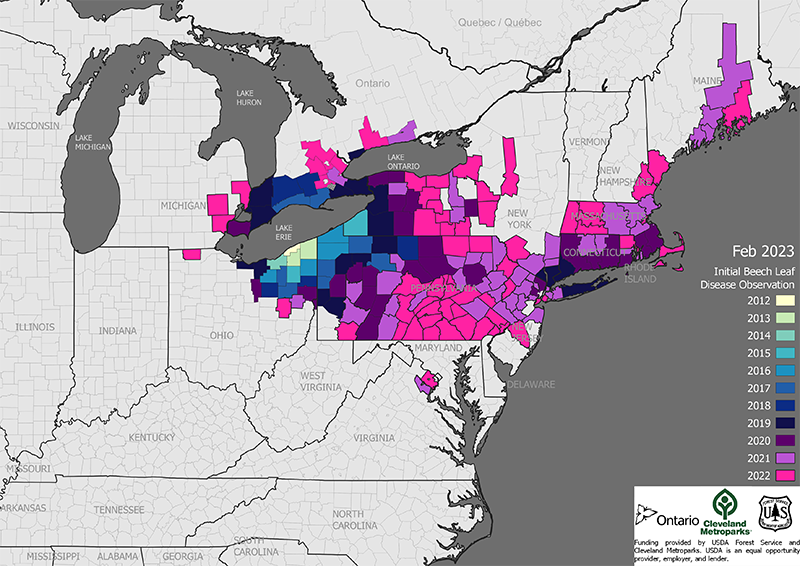

BLD was first identified in North America in the Cleveland, Ohio area in 2012. Since that time, BLD has been spreading in a mostly northeasterly direction, reaching Maine in 2021. This map shows its progress year-by-year.

As BLD has been present in North America for such a relatively short period, there are still many unanswered questions about causative factors, disease development, disease transmission and outcomes for infected trees. In Ohio and parts of Ontario where it has been present for about a decade, tree mortality may occur within 2 to 7 years for trees of all age categories, but younger trees appear more susceptible. It still remains to be seen how the disease will play out in Maine. Based on three years of anecdotal observations on our property in Lincolnville, early season impacts seemed significantly more severe during the second year than for the first, but the third year has been similar to the second year, so far.

The Maine Forest Service has set up a long term monitoring plot in our woodlot where it will more quantitatively track the course of BLD over time.

While the cause of the disease has not been determined definitively, there is a strong association with the presence of a subspecies of a non-native microscopic roundworm, the nematode Litylenchus crenate mccannii. This nematode is often accompanied by specific species of fungi and bacteria which also may play a role in the infection. The life cycle of the nematode has not been fully documented, but it is present in the winter buds, likely initiating damage to the developing leaves. Thousands of nematodes may be present in a single infected leaf, interfering with its ability to photosynthesize and leading to leaf senescence and early leaf fall.

One of the mysteries associated with BLD is its means of transmission across the landscape. It has been spreading northeast at a rate of about 60 miles/year over the past decade, but the mode of this transmission has not been determined. There are several hypotheses including wind, migratory birds, movement of infected nursery stock, contaminated soil, or transport of Beech branches, wood chips or compost. Experimentation has shown that the nematodes can survive the passage through the guts of birds and a number of bird species do eat Beech leaf buds which can contain BLD nematodes.

Until the modes of transport are more fully understood, the Maine Forest Service recommends not moving Beech branches, twigs, leaves, seedlings or nursery stock from affected areas; inspection of nursery stock for BLD symptoms before purchase; and avoidance of moving soil or organic matter from affected areas. For trail users in our area, it would be wise to clean footwear soles of dirt and mud before using the footwear again in unaffected areas. These actions may help slow the spread of BLD. Currently, there are no known treatments that are available that can address BLD on a landscape level scale, however there is a treatment that has shown promise for individual trees.

Beech trees are an important constituent of our woodlands in Midcoast Maine and, in some tracts, they represent the most prevalent tree species. Coastal Mountain’s Beech Hill Preserve is, of course, named for the American Beech and Beeches can be found in most of the wooded preserves. While Beech trees have been affected significantly by another non-native disease complex, Beech Bark Disease, which limits the growth and longevity of the trees, Beech still provides tremendous benefits for the forested ecosystem. Beechnuts, produced in the fall, are highly nutritious with copious levels of protein and fat. They are a mainstay for many animal species including Black Bears, flying squirrels, Red Squirrels, Gray Squirrels, Porcupines, Ruffed Grouse, Turkeys and Blue Jays. Fallen Beech leaves are relatively slow to decompose and thus contribute to the leaf litter layer of the forest, providing important habitat for insect species, salamanders, small mammals, and ground nesting birds. This leaf litter layer also helps protect forest soils from erosion and may help prevent the establishment of some invasive plant species in the forest understory.

Looking at the bigger picture, the impacts of the potential loss of the American Beech in our woodlands need to be considered in the context of other ecologically important tree species which have faced or will be facing similar threats. The American Chestnut and American Elm are either extirpated or greatly reduced throughout much of their range, but in the case of both species, disease resistant hybrids have been developed that may provide similar ecosystem functions. The Woolly Adelgid has now reached the Midcoast, including at least one Coastal Mountain Land Trust preserve, and it is poised to devastate our Eastern Hemlocks, as it has in much of its range to our south, stretching down to the Great Smoky Mountains. There are now two species of predatory beetles available which attack the Woolly Adelgid and may help blunt its impact on our Hemlocks. Finally, our ash trees are threatened by the Emerald Ash Borer which is at our doorstep. It is already in Maine, both to our south and to our north. Estimates are that the Emerald Ash Borer has already killed over 100 million ash trees over the past 20 years across the United States and Canada. Experimental trials are underway to assess the effectiveness of several species of parasitic wasps in limiting the damage caused by the Emerald Ash Borer. Whether or not there are similar remedies that might address BLD is currently unknown.

These tree species have been an integral and sustaining part of our native ecosystems for thousands of years. Coastal Mountain Land Trust, with its network of forever preserves, is well situated to give thoughtful consideration to strategic management actions, as it has in the past, that might help maximize the survival of these important tree species on its own lands and beyond.

For those readers who are interested in learning more about Beech Leaf Disease, the Maine Forest Service has an excellent, well illustrated website dedicated to the topic that is linked here.

Also, the Maine Monitor has published an informative article entitled “Can’t save the forest for the trees: Confronting the loss of species that define Maine woodlands”, July 29, 2022, by Marina Schauffler which is linked here.

Finally, I would like to acknowledge and thank Dr. Aaron Bergdahl of the Maine Forest Service and Dr. Cameron McIntire of the U.S. Forest Service for their expertise and responsiveness in identifying and helping us understand Beech Leaf Disease in our woodland.